In your emails, getting your hashes

Capturing NetNTLM hashes from network communications is nothing new; a quick Google for ‘Capture NTLM Hashes’ throws up blog posts discussing the various ways to force SMB communications to an attacker and the numerous existing tools to capture the authentication attempt and extract the password hash. Sniffing SMB traffic requires elevated permissions that typically aren’t available when you first get command and control on your target and being a ‘yes’ person for NetBIOS queries can be a little noisy. This blog post will discuss the concept of Windows ‘Trust Zones’, how email signatures are configured in Outlook and how the combination of the two can result in the capture of hashes. The focus will be on achieving this in a red team scenario, which means ticking the following boxes:

- Can be performed without GUI access

- Minimal impact to the user experience

- Repeatable and automated

- Easily reversible (Any changes to files/settings put back to the original state)

Windows Trust Zones

In order to capture hashes, software on the target system must be forced to attempt a type authentication to the attacker using the currently authenticated account. As well as SMB, other protocols can also support authentication with the user’s NetNTLM hash over the network:

- HTTP

- POP3

- SMTP

On previous engagements internal phishing emails for both credential capture, and malicious documents for establishing command and control have been highly successful, however this level of overtness can lead to detection, particularly when close colleagues are targeted. Capturing and cracking hashes requires less user interaction and therefore has a lower detection rate. A typical internal phishing email targeting SMB would contain HTML content similar to the following:

When this does not point to a valid resource, accessible over SMB by the target, Outlook informs the user that it’s struggling to retrieve the data but the connection attempt is enough to capture the target user’s password hash if (and it’s a big if) administrative permissions have been gained on a machine accessible by the target.

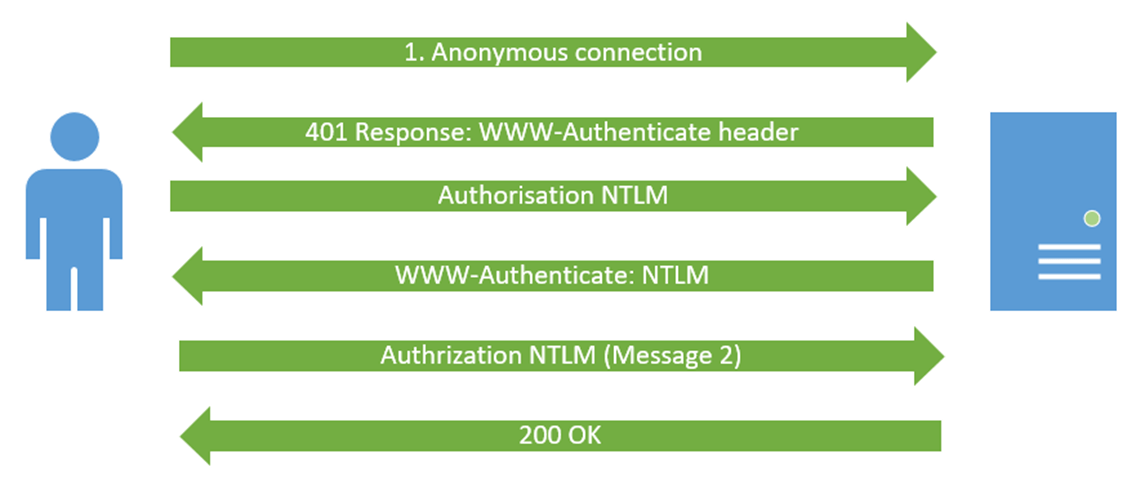

So using SMB links doesn’t satisfy the requirements for stealth, or the ability to act without already elevated permissions. This doesn’t mean we can’t use tags to capture hashes though, it just needs to be over HTTP. HTTP NetNTLM authentication can be requested by the server, to which the web browser (or other web-enabled client) will cause the web browser to engage in a challenge/response communication that, if captured can be subjected to offline cracking to obtain the user’s plain text password – the image below shows the authentication flow at a high level:

In order to prevent nefarious servers on the internet from simply requesting this type of authentication, Microsoft introduced the concept of trust zones. In order of least restrictive to most restrictive, these zones are:

- My Computer

- Local Intranet Zone

- Trusted sites Zone

- Internet Zone

- Restricted Sites Zone

So if you’re trying to authenticate to something on the local intranet then the browser will happily send your password hash, allowing single sign-on but if evil.com asks for the hash, it will be classed as ‘Internet Zone’ and therefore won’t receive it.

Get in the Zone

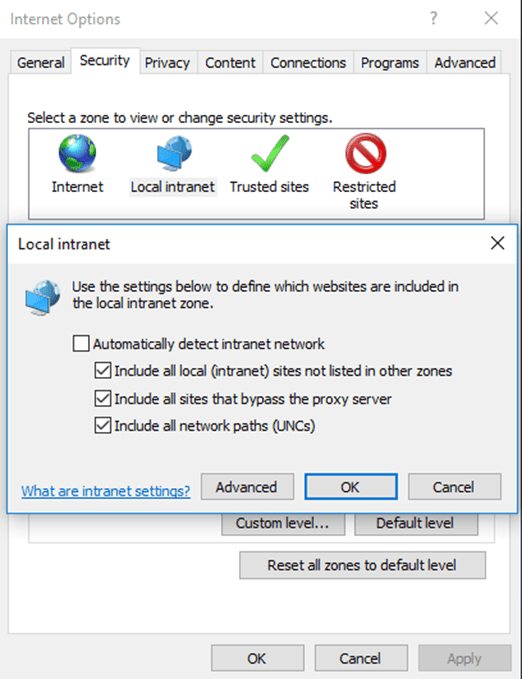

So how does Windows know whether the server requesting the authentication is in the Local Intranet Zone? As well as being able to add specific sites to a zone, Internet Options also has some default patterns that will cause a resource to be classed as Intranet:

This results in the following outcomes when running through the various different ways of requesting the same HTTP resource:

| Type | URL | Zone Classification | Outcome |

| IP Address | http://192.168.10.10/index.html | Internet | User is prompted for a username and password |

| FQDN* | http://webserver.targetorg.local/index.html | Internet[J1] | User is prompted for a username and password |

| NetBIOS Name | http://webserver/index.html | Intranet | NTLM Authentication is attempted with the currently authenticated user’s credentials |

*Though this is the default setting, many organisations will add the FQDN of the internal domain to the Intranet zone.

So if we can force a HTTP request using a NetBIOS name from a domain joined machine to a web server that captures authentication attempts, then we end up with a password hash to crack. This is all very familiar to anyone who has used Responder, or Inveigh although perhaps SMB is the more popular protocol, combined with NetBIOS name spoofing. The benefits of HTTP over SMB are:

- A HTTP server can listen on any port – important for low integrity command and control

- Doesn’t require elevated privileges to sniff traffic on Windows; it’s a running service, not capturing communications to an existing service as Inveigh does with SMB.

These benefits are huge and ripe for abuse on most red team engagements, particularly given on most engagements:

- Initial access is on a low privileged end user device (so we can still use this)

- Most organisations still have a relatively flat network (all hosts can communicate with each other – even over the VPN!)

- Host based firewalls are often off or configured very permissively when in the ‘Domain’ profile

- There are a number of ways to elicit HTTP traffic to a destination

Outlook Security

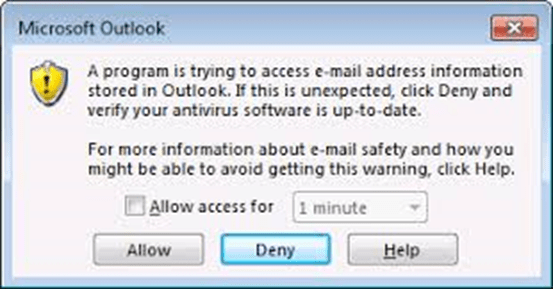

When operating through a command and control channel, sending an email using the target’s account becomes more complex. There’s always the option of stealing some Office365 cookies, or browser pivoting through the beacon but attempts to use a web based interface but it’s always nice to be able to operate without the requirement for a GUI. Attempting to use Microsoft.Office.Interop.Outlook in C# can result in a sudden and rather worrying prompt for the user:

By default, the decision whether to display this prompt is bizarrely made by checking whether the current anti-virus software is out-of-date. If it’s not then the prompt is not shown; an extract from the Outlook Programmatic Access documentation is shown below:

The Programmatic Access security settings in the Trust Center provide the following options:

| Setting | Meaning |

| Warn me about suspicious activity when my antivirus software is inactive or out-of-date (recommended) | This is the default setting in Outlook. Suspicious activity refers to an untrusted program that is trying to access Outlook. |

| Always warn me about suspicious activity | This is the most secure setting and you’ll always be prompted to make a trust decision when a program attempts to access Outlook. |

| Never warn me about suspicious activity (not recommended) | This is the least secure setting. This means that with a few pre-flight checks, sending out internal phishing emails can be fairly trivial and the default Trust Centre settings mean that any images included within HTML content will be automatically downloaded. |

So this means that the email content would now become:

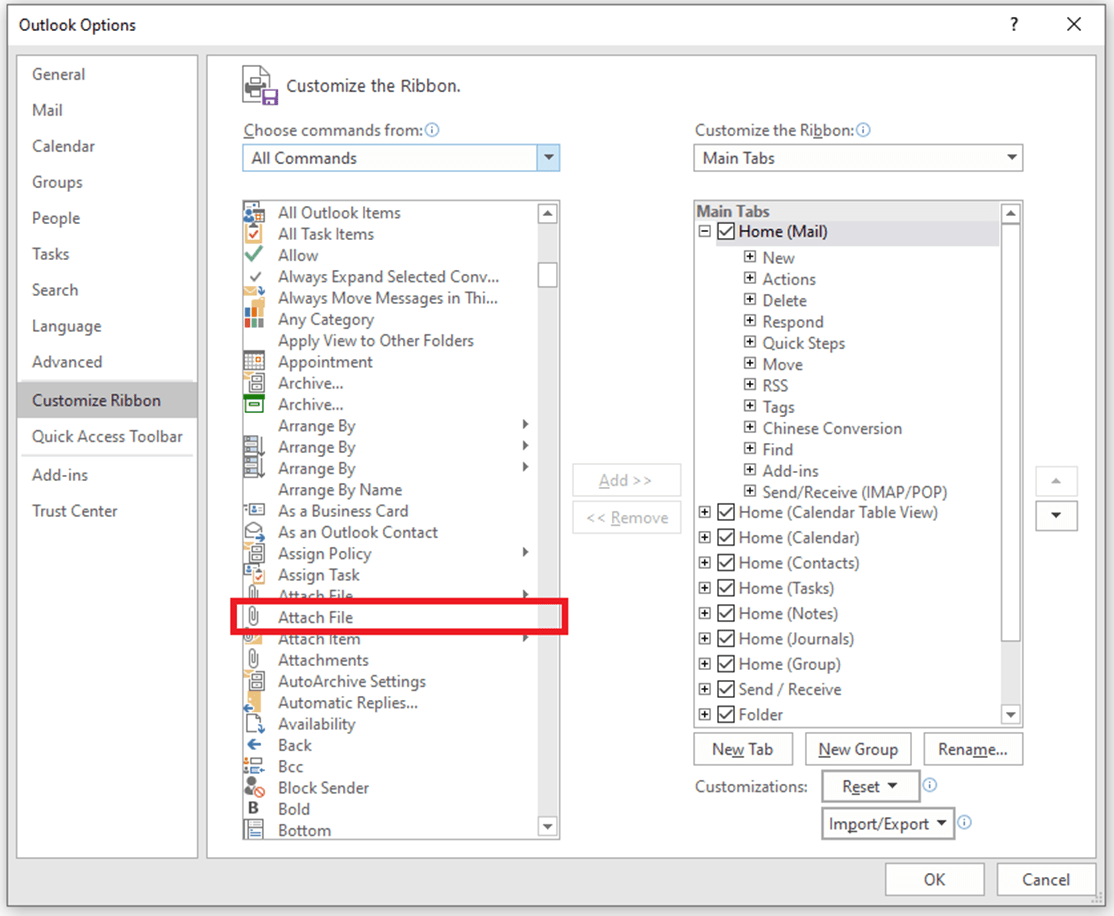

Given GUI access to a target, it is possible to insert the HTML content using Outlook, although this seems to require the addition of an alternative “Attach File” menu item to give the required option. This can be achieved by modifying the ribbon to include the duplicate “Attach File” as shown below:

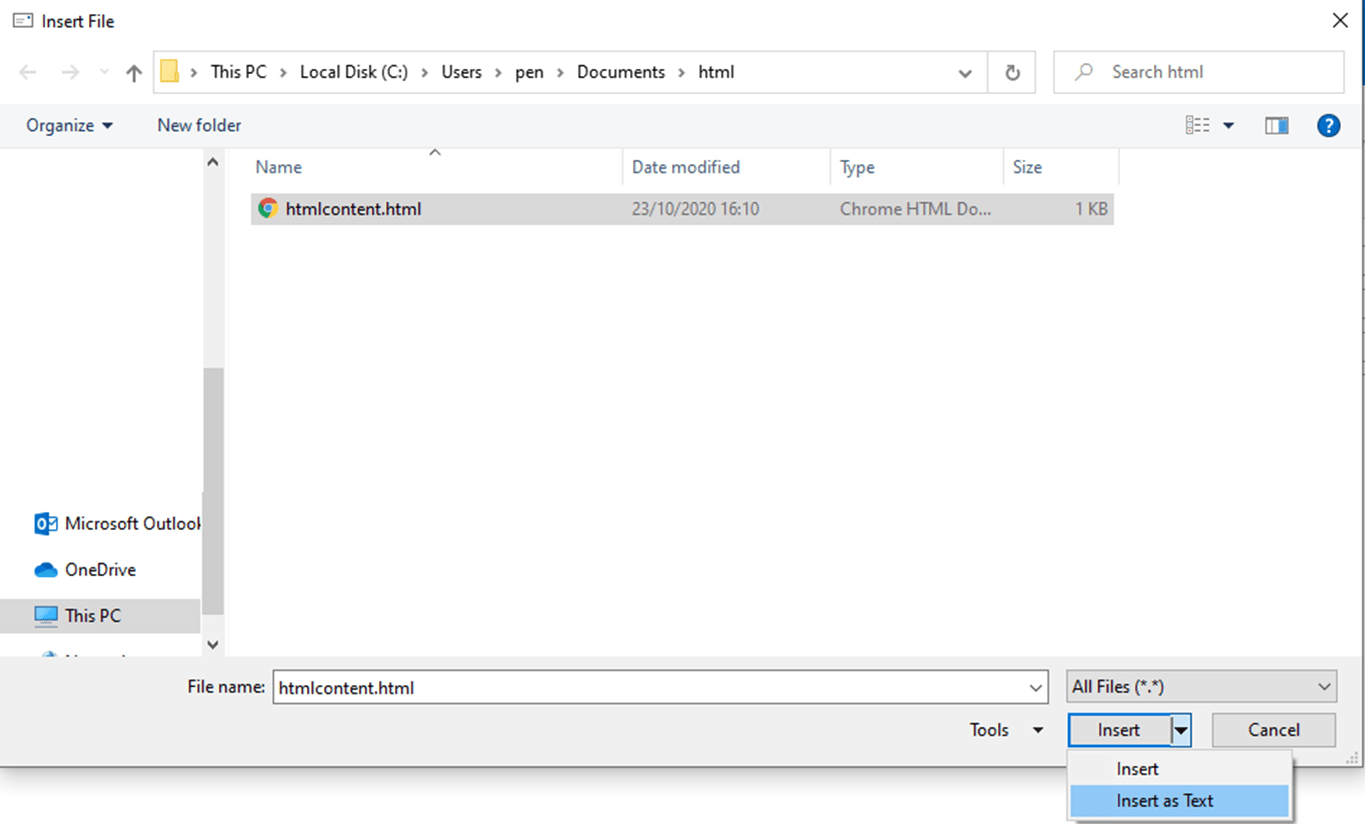

When composing a new email message, the newly added “Attach File” menu offers the option to insert a HTML file as text, which results in the content being included and rendered in the email body.

But what if we don’t have GUI access, and if the user has security settings that prevent code from interacting with Outlook Interop?

Sign Me Up!

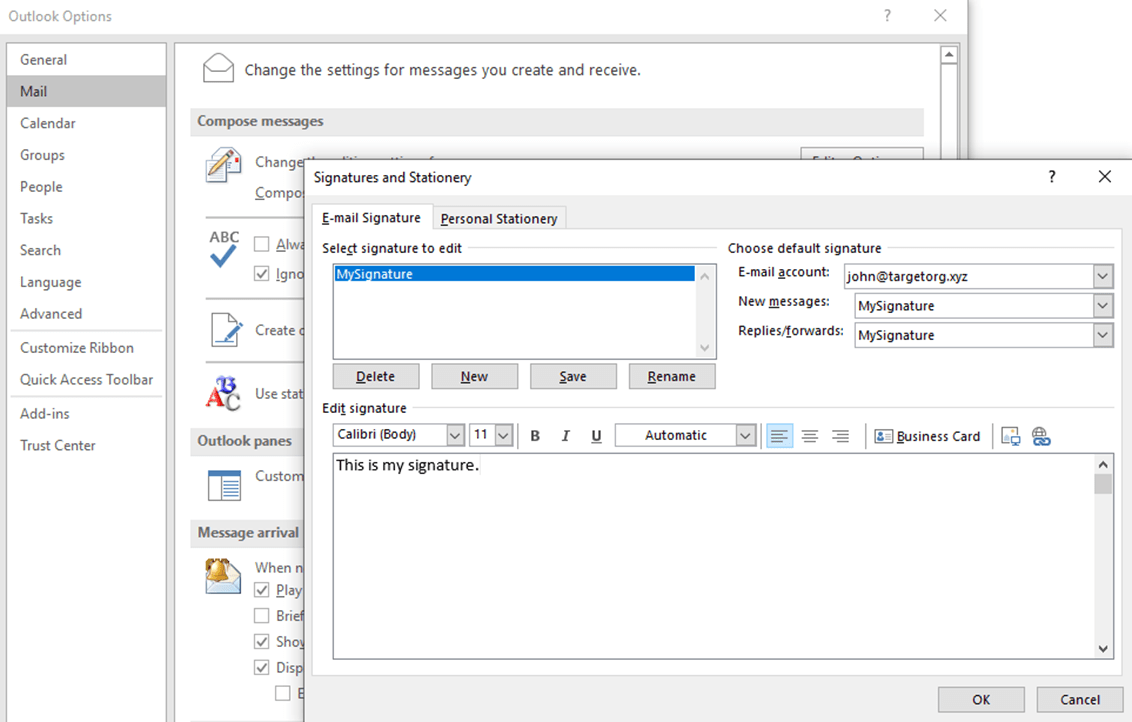

Email Signatures can be defined from within Outlook via the Options > Mail > Signatures menu, as shown below:

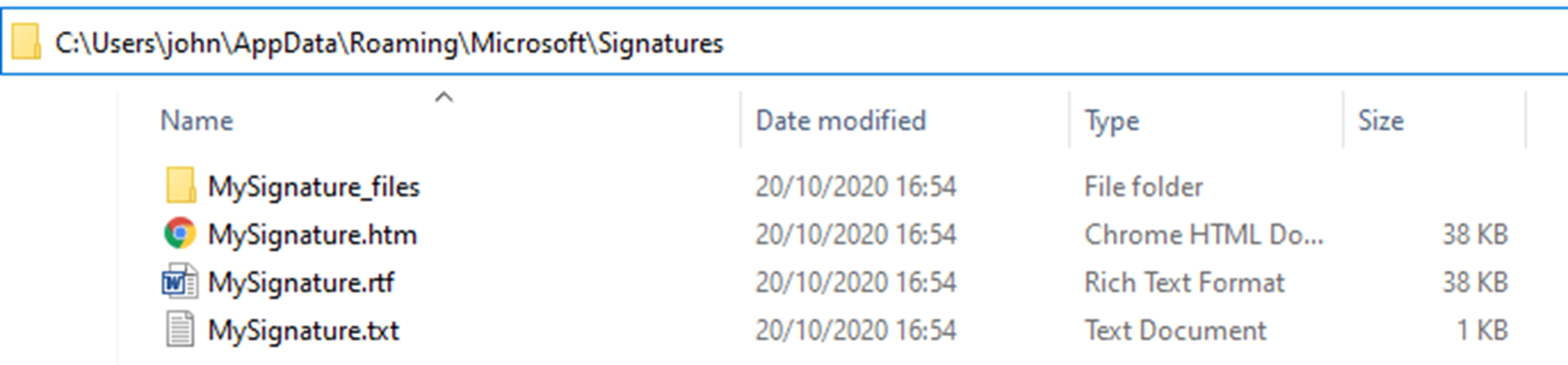

Creating a signature results in the content being used to generate three files types in the user’s AppData folder that correspond to the various email formats; plain text, Rich Text and HTML:

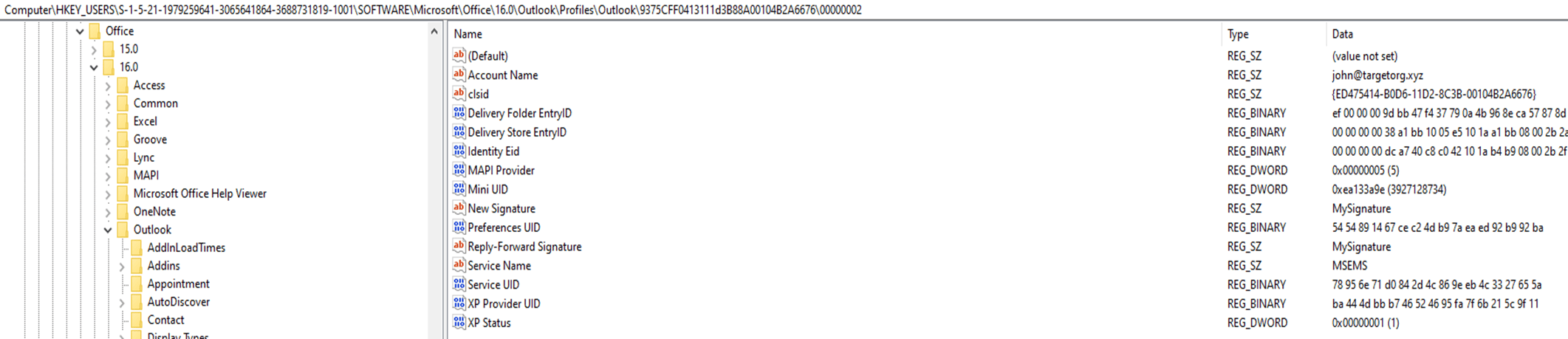

These files are then referenced in different places within the registry depending on whether the signature has been defined by the end user, or pushed via policy

| Action | Registry Key | Values |

| User Defined Signature | ComputerHKEY_USERS | New Signature Reply-Forward Signature |

| Policy Defined Signature | ComputerHKEY_USERS | NewSignature ReplySignature |

So with some quick logic we can see whether a user has signatures set, or not. If it’s not set, we can set one on the user’s behalf through creation of the relevant files within the signatures folder (C:UsersUserAppDataRoamingMicrosoftSignatureMySignature.htm), or modify an existing signature if one is already set.

Simply adding a 1×1 pixel image to the signature will achieve the desired results.

To automate the process of modifying the signature and starting a corresponding listener, a tool was written in C#, borrowing code from the Seatbelt and Inveigh projects. The tool features are:

- Queries the firewall for suitable ports to listen on (Uses some seatbelt code)

- Cross references HttpQueryServiceConfiguration for any usable URL ACLs

- Starts TCP/HTTP server for hash capture (Uses Inveigh code)

- Signature Detection (to modify the appropriate registry settings and signatures)

- Modification of Signature

- Option to send mail to a specific AD group (e.g. domain admins)

- Option to create encrypted logs on disk

- Cleanup (Reverts changes in signature settings and existing signature)

*Tool sold as seen/ “Works on my box” –

Published on github at: https://github.com/nccgroup/nccfsas/blob/main/Tools/Sigwhatever

The use of the tool (except potentially use of the send mail feature) should not impact the user experience or make any visible changes (just don’t look really closely for the 1x1px image )

There are some potential downsides for this attack which you should be aware of prior to use:

- External recipients would also receive the tracking image in the signature, revealing an internal hostname.

- If targeted users access the emails at a later date – this will still trigger a request to be sent, so this could be picked up by another attacker at a later date (in the highly unlikely event that the same host is compromised, and an attacker decides to attempt hash capture on the same port).

- Expediting the attack by sending unsolicited emails with the modified signatures may be suspicious.

Detection and Prevention

There are number of mitigations which would prevent this attack, all of which are generally sensible hardening steps to hosts which we advise

- Network Segregation – As always, internal network segregation can help to reduce the effectiveness of this kind of technique. Allowing only essential communication between end user devices would make the service listening for hashes inaccessible.

- Host based firewalls – Turn them on, and prevent additional services from listening

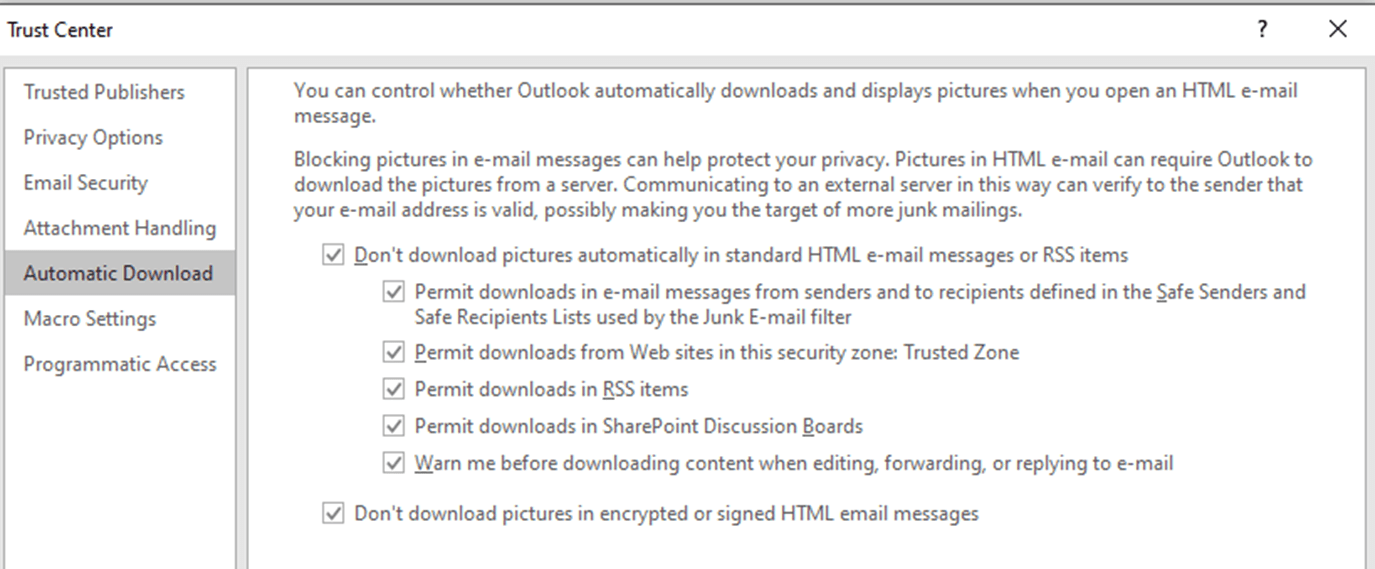

- Turn off auto-download of images, or default to plain text email (this is default for emails from outside the organisation, but HTML is displayed for email sent within the same organisation)

- Monitor for changes to the relevant registry keys from processes other than Outlook.exe

Plain Text Email

Defaulting to rendering emails in plain text for both received communications and composition would prevent Outlook from rendering the HTML in the signature. This can be achieved on a single machine via the following options:

Composition:

Outlook Options -> Mail -> Compose messages in this format

Received Email:

Outlook Options -> Trust Center -> Email Security -> Read all standard mail in plain text

This can also be set via Group Policy with the correct admin templates installed:

Composition:

User Configuration -> Policies -> Administrative Templates -> Microsoft Outlook

Received Email:

User Configuration -> Policies -> Administrative Templates -> Microsoft Outlook

This obviously has an impact on the formatting and readability of email content but can be overridden by the end user on a per-email basis.

Credits: David Cash, Julian Storr, Richard Warren