As the name suggests, multivariate cryptography refers to a class of public-key cryptographic schemes that use multivariate polynomials over a finite field. Solving systems of multivariate polynomials is known to be NP-complete, thus multivariate constructions are top contenders for post-quantum cryptography standards. In fact, 11 out of the 50 submissions for NIST’s call for additional post-quantum signatures are multivariate-based. Multivariate cryptography schemes have received new interest in recent years due to the push to standardize post-quantum primitives. Sadly, the resources available online to learn about multivariate cryptography seem to fall into one of two categories, high level overviews or academic papers. The former is fine for getting a feel for the topic, but does not give enough details to feel fully satisfied. On the other hand, the latter is chock full of details, and is rather dense and complex. This blog post aims to bridge the gap between the two types of resources by walking through an illustrative example of a multivariate digital signature scheme called Unbalanced Oil and Vinegar (UOV) signatures. UOV schemes serve as the basis for a number of contemporary multivariate signature schemes like Rainbow and MAYO. This post assumes some knowledge of cryptography (namely what a digital signature scheme is), the ability to read some Python code, and a bit of linear algebra knowledge. By the end of the post the reader should not only have a strong conceptual grasp of multivariate cryptography, but also understand how a (toy) implementation of UOV works.

Preliminaries

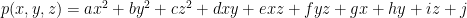

A multivariate quadratic (which is the degree of polynomial we concern ourselves with in multivariate cryptographic schemes) is a quadratic equation with with two or more indeterminates (variables). For instance a multivariate quadratic equation (MQ) with three indeterminates can be written as:  where at least one of the second degree terms

where at least one of the second degree terms  is not equal to

is not equal to  . With a MQ defined we can now describe the hard problem on which the security of MQ cryptography schemes are based – the so-called MQ problem.

. With a MQ defined we can now describe the hard problem on which the security of MQ cryptography schemes are based – the so-called MQ problem.

MQ Problem

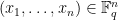

Given a finite field of  elements

elements  and

and  quadratic polynomials

quadratic polynomials ![p_1,\ldots,p_m \in \mathbb{F}_q[X_1,\ldots,X_n]](/media/l0lbvmyb/_p_1-ldots-p_m-in-mathbb-f-_q-x_1-ldots-x_n.png) in

in  variables for

variables for  , find a solution

, find a solution  of the system of equations. That is for

of the system of equations. That is for  we have

we have  . The MQ problem is known to be NP-complete, and it is thought that quantum computers will not be able to solve this problem more efficiently than classical computers. However, in order to be able to design secure cryptographic schemes based on the MQ problem, we need to find a trapdoor that allows a party with some private information to efficiently solve the problem. This is like knowing the factorization of the modulus

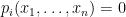

. The MQ problem is known to be NP-complete, and it is thought that quantum computers will not be able to solve this problem more efficiently than classical computers. However, in order to be able to design secure cryptographic schemes based on the MQ problem, we need to find a trapdoor that allows a party with some private information to efficiently solve the problem. This is like knowing the factorization of the modulus  in RSA or the discrete-log in Diffie-Hellman key exchange. Generally, in multivariate public key signature schemes we define the public verification key

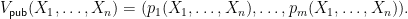

in RSA or the discrete-log in Diffie-Hellman key exchange. Generally, in multivariate public key signature schemes we define the public verification key  as an ordered collection of

as an ordered collection of  multivariate quadratic polynomials in

multivariate quadratic polynomials in  variables over a finite field

variables over a finite field  for

for  . That is

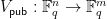

. That is ![\mathsf{pub} = p_1,\ldots,p_m \in \mathbb{F}_q [X_1,\ldots,X_n]](/media/e4mawkqh/_-mathsf-pub-p_1-ldots-p_m-in-mathbb-f-_q-x_1-ldots-x_n.png) . The verification function is then a polynomial map

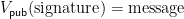

. The verification function is then a polynomial map  such that:

such that:  Note that our signatures will be of length

Note that our signatures will be of length  and messages (or likely in practice a hash of the message we are signing) will be encoded as

and messages (or likely in practice a hash of the message we are signing) will be encoded as  field elements in

field elements in  . One simply verifies signatures by ensuring that

. One simply verifies signatures by ensuring that  for some message corresponding to the signature. The secret key (singing key)

for some message corresponding to the signature. The secret key (singing key)  is then some data on how

is then some data on how  is generated that makes it easy to invert

is generated that makes it easy to invert  and generate a valid signature for a given message. Generating a valid signature for a given message without knowledge of the secret key is exactly an instance of the MQ problem, and thus should be hard for even a quantum-capable adversary. However, we need special structure of

and generate a valid signature for a given message. Generating a valid signature for a given message without knowledge of the secret key is exactly an instance of the MQ problem, and thus should be hard for even a quantum-capable adversary. However, we need special structure of  to ensure that a trapdoor exists so that parties with knowledge of

to ensure that a trapdoor exists so that parties with knowledge of  be easily able to sign messages. This reduces the problem space, and thus may lead to vulnerabilities in multivariate cryptography schemes. One such design that seems to have remained secure despite years of thorough cryptanalysis is Unbalanced Oil and Vinegar signatures. We will describe the scheme in the next section and present a toy implementation and a walkthrough to see how the inner mechanisms of the scheme work.

be easily able to sign messages. This reduces the problem space, and thus may lead to vulnerabilities in multivariate cryptography schemes. One such design that seems to have remained secure despite years of thorough cryptanalysis is Unbalanced Oil and Vinegar signatures. We will describe the scheme in the next section and present a toy implementation and a walkthrough to see how the inner mechanisms of the scheme work.

Unbalanced Oil and Vinegar Signatures

Unbalanced Oil and Vinegar (UOV) multivariate signatures were fist introduced by Kipnis, Patarin, and Goubin in 1999. One can find the original paper here. UOV is based on an earlier scheme, Oil and Vinegar signatures introduced by Patarin in 1997. The earlier scheme was broken by a structural attack discovered by Kipnis and Shamir in 1998. However, with a slight variation of the original scheme the UOV signature scheme was created and is thought to be secure. We will now go through the parts of the signature algorithm.

UOV Paramters

We choose a small finite field  , where we usually select

, where we usually select  for some small power

for some small power  . The

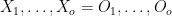

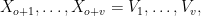

. The  input variables

input variables  are divided into two ordered collections, the so-called oil and vinegar variables:

are divided into two ordered collections, the so-called oil and vinegar variables:  and

and  respectively, with

respectively, with  . The message to be signed or (likely the hash of said message) is represented as an element in

. The message to be signed or (likely the hash of said message) is represented as an element in  and is denoted

and is denoted  . The signature is then represented as an element of

. The signature is then represented as an element of  and is denoted

and is denoted  .

.

Private (Signing) Key

Our secret key is a pair  . We take

. We take  to be a bijective and affine function such that

to be a bijective and affine function such that  . For our purposes we can take the meaning of affine to be that the outputs of the function can be expressed as polynomials of degree one in the

. For our purposes we can take the meaning of affine to be that the outputs of the function can be expressed as polynomials of degree one in the  indeterminates and that our coefficients on such inputs are in the field

indeterminates and that our coefficients on such inputs are in the field  . Then,

. Then,  (also referred to as the central map) is an ordered collection of

(also referred to as the central map) is an ordered collection of  functions that can be expressed in the form:

functions that can be expressed in the form:  where

where ![k \in [1 \ldots o]](/media/3hebj00n/_k-in-1-ldots-o.png) . The coefficients

. The coefficients  are selected randomly and are kept secret. Note, that vinegar variables “mix” quadratically with all other variables, but oil variables never “mix” with themselves. That is there are no

are selected randomly and are kept secret. Note, that vinegar variables “mix” quadratically with all other variables, but oil variables never “mix” with themselves. That is there are no  terms, hence the name of the scheme (although one might observe that this is not how actual salad dressing actually works).

terms, hence the name of the scheme (although one might observe that this is not how actual salad dressing actually works).

Public (Verification) Key

Let  be an element of

be an element of  defined in the style of our input

defined in the style of our input  . We then transform

. We then transform  into

into  , where

, where  is our secret function. Each function

is our secret function. Each function  ,

, ![k \in [1 \ldots o]](/media/3hebj00n/_k-in-1-ldots-o.png) , can be written as a polynomial

, can be written as a polynomial  of total degree two in the

of total degree two in the  unknowns,

unknowns, ![z \in [1 \ldots n]](/media/muog4jag/_z-in-1-ldots-n.png) where

where  . We denote our public key,

. We denote our public key,  , as the ordered collection of these

, as the ordered collection of these  polynomials in

polynomials in  unknowns:

unknowns: ![\forall k \in [1 \ldots o] \tilde{f}_{k} = P_{k}((z_1,\ldots,z_n)).](/media/ybhp2eg3/_-forall-k-in-1-ldots-o-tilde-f-_-k-p_-k-z_1-ldots-z_n.png) That is to say we compose

That is to say we compose  with

with  ,

,  . We will elucidate how this computation is actually done in our illustrative example.

. We will elucidate how this computation is actually done in our illustrative example.

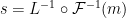

Signing

We solve for a signature  such that

such that  (where

(where  ) of message

) of message  (or hash of the message)

(or hash of the message)  in the following way. 1. Select random vinegar values

in the following way. 1. Select random vinegar values  and substitute them into each of the

and substitute them into each of the  equations in

equations in  . 2. We then are left to find the

. 2. We then are left to find the  unknowns

unknowns  that satisfy

that satisfy  . This is a linear system of equations in the oil variables, as we have no

. This is a linear system of equations in the oil variables, as we have no  terms in our private key. This can be solved using Gaussian elimination. 3. If the system is indeterminate, return to step 1. 4. Compute the signature of

terms in our private key. This can be solved using Gaussian elimination. 3. If the system is indeterminate, return to step 1. 4. Compute the signature of  as

as  . In brief, we invert

. In brief, we invert  (solve the MQ problem) by using the secret structure of $\latex P$, i.e. the fact it is the composition of two linear functions, which are both easy to invert if you know said functions.

(solve the MQ problem) by using the secret structure of $\latex P$, i.e. the fact it is the composition of two linear functions, which are both easy to invert if you know said functions.

Verification

The recipient simply checks that  .

.

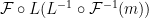

Correctness

Recall that our verification key is  , and the signing key is

, and the signing key is  . Our signature is of the form

. Our signature is of the form  . Then we can show

. Then we can show

as desired.

as desired.

Security Considerations

As aforementioned the original Oil and Vinegar scheme is broken. That is, the case where  (or when they are quite close) is broken by the structural attack of Kipnis and Shamir. For

(or when they are quite close) is broken by the structural attack of Kipnis and Shamir. For  the scheme is not secure because of efficient algorithms to solve heavily under-determined quadratic systems. The current recommendation, for which no technique is known to reduce the difficulty of solving the MQ problem, is to set

the scheme is not secure because of efficient algorithms to solve heavily under-determined quadratic systems. The current recommendation, for which no technique is known to reduce the difficulty of solving the MQ problem, is to set  or

or  . Therefore, the scheme we examine is called Unbalanced due to the fact

. Therefore, the scheme we examine is called Unbalanced due to the fact  .

.

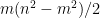

Advantages and Problems of UOV

UOV, in addition to being thought to be quantum-resistant, provides very short signatures as compared to other post-quantum signature schemes like lattice-based and hash-based schemes. Moreover, the actual computational operations (while seemingly complex) only require additions and multiplications of small field elements that are fast and simple to implement even on constrained hardware. The largest issue with the UOV scheme is the size of the public keys. One needs to store approximately  coefficients for public keys. Techniques exist to expand about

coefficients for public keys. Techniques exist to expand about  of the coefficients for the public key from a short seed, such that we only need to store

of the coefficients for the public key from a short seed, such that we only need to store  coefficients. However, this is still a very large public key – about 66KB for 128 bits of security compared to just a 384 byte key for RSA at the same security level or a 1793 byte key for the lattice based scheme Falcon at a higher security level. Some modern candidates that use UOV as a base and how they go about trying to solve this key size problem will be discussed in the concluding remarks of this post

coefficients. However, this is still a very large public key – about 66KB for 128 bits of security compared to just a 384 byte key for RSA at the same security level or a 1793 byte key for the lattice based scheme Falcon at a higher security level. Some modern candidates that use UOV as a base and how they go about trying to solve this key size problem will be discussed in the concluding remarks of this post

Illustrative Example

To illustrate how the UOV signatures work we implemented a toy implementation of a UOV scheme in Python3. The code is available here. It goes without saying that it is just for educational purposes and should not be used in any application desiring any real level of security. We will walk through the signing process step-by-step stopping to examine all values and intermediaries. We use NumPy to store polynomials in quadratic form, store our secret trapdoor linear transformation  , and to do linear algebra. We do note that the our UOV implementation is a slight simplification of the general description we give above. We discuss this next.

, and to do linear algebra. We do note that the our UOV implementation is a slight simplification of the general description we give above. We discuss this next.

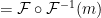

Simplification

In our above presentation of the UOV scheme we define our central map  such that it contains not only quadratic terms, but also linear and constant terms. As a result, the public verification key

such that it contains not only quadratic terms, but also linear and constant terms. As a result, the public verification key  also contains said terms. For the simplified variant we set these linear and constant terms to

also contains said terms. For the simplified variant we set these linear and constant terms to  , and are left with only non-zero quadratic terms, that is our central map

, and are left with only non-zero quadratic terms, that is our central map  is a collection of homogenous polynomials of degree two. This simplified variant

is a collection of homogenous polynomials of degree two. This simplified variant  is an ordered collection of

is an ordered collection of  functions that can be expressed in the form:

functions that can be expressed in the form:  where

where ![k \in [1 \ldots o]](/media/3hebj00n/_k-in-1-ldots-o.png) and all coefficients are in

and all coefficients are in  . This simplification presents a number of advantages. Namely, the components

. This simplification presents a number of advantages. Namely, the components  of

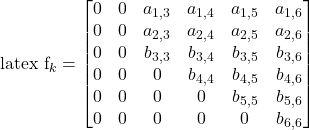

of  can we written as an upper triangular matrix in

can we written as an upper triangular matrix in  of quadratic forms. For the below example we set

of quadratic forms. For the below example we set  .

.

Note that oil variables do not mix, so we have a block zero matrix in the upper-left of this representation. Further, this allows us to define our secret transformation  to be in

to be in  where GL is the general linear group. That is (for our purposes)

where GL is the general linear group. That is (for our purposes)  is an invertible matrix with dimensions

is an invertible matrix with dimensions  and entries in our field

and entries in our field  . One can always turn a homogenous system of polynomial equations in

. One can always turn a homogenous system of polynomial equations in  variables into an equivalent system of

variables into an equivalent system of  variables by fixing one of the variables to $1$. In the reverse this process is called homogenization. Thus, we still preserve the structure of the UOV signing key with this simplification. In turn, from the point of view of a key-recovery attack the security of this simplified variant of UOV is equivalent to that of original UOV with

variables by fixing one of the variables to $1$. In the reverse this process is called homogenization. Thus, we still preserve the structure of the UOV signing key with this simplification. In turn, from the point of view of a key-recovery attack the security of this simplified variant of UOV is equivalent to that of original UOV with  indeterminates..

indeterminates..

Parameters

A note on presentation: As opposed to above where we used  typesetting for math, we will keep our mathematical notation in the prose in line with our choices in the code. That is we will use inline code blocks to typeset variable names and math (i.e.

typesetting for math, we will keep our mathematical notation in the prose in line with our choices in the code. That is we will use inline code blocks to typeset variable names and math (i.e. F is our central map.) We will work over the field GF(256). We use the galois package to do array arithmetic and linear algebra over the field. For more information about how to do arithmetic in Galois (finite) fields see this Wikipedia page. For this example we set o=3 and v=2o=6. These parameters are far to small to provide actual security, but work nicely for our illustrative example. Below is the parameter information our implementation spits out.

Galois Field:

name: GF(2^8)

characteristic: 2

degree: 8

order: 256

irreducible_poly: x^8 + x^4 + x^3 + x^2 + 1

is_primitive_poly: True

primitive_element: x

The parameters are o=3 and v=6.

Key Generation

Private (Signing) Key

To generate the central map F generate o random multivariate polynomials in the style described in the simplified UOV scheme. Each polynomial is stored as a n x n = (o+v) x (o+v) NumPy matrix. The complete central map is a o-length list of these matrices.

def generate_random_polynomial(o,v):

f_i = np.vstack(

(np.hstack((np.zeros((o,o),dtype=np.uint8),np.random.randint(256, size=(o,v), dtype=np.uint8))),

np.random.randint(256, size=(v,v+o),dtype=np.uint8))

)

f_i_triu = np.triu(f_i)

return GF256(f_i_triu)

def generate_central_map(o,v):

F = []

for _ in range(o):

F.append(generate_random_polynomial(o,v))

return F

To generate our secret transformation L, we generate a random n x n matrix and ensure that it is invertible, as this will be necessary to compute signatures.

def generate_affine_L(o,v):

found = False

while not found:

try:

L_n = np.random.randint(256, size=(o+v,o+v), dtype=np.uint8)

L = GF256(L_n)

L_inv = np.linalg.inv(L)

found = True

except:

found = False

return L, L_inv

Then, we have a wrapper function that generates our private key using the above functions as the triple (F, L, L_inv). We deviate from the standard definition of the signing key by also storing the inverse of L, denoted L_inv.

def generate_private_key(o,v):

F = generate_central_map(o,v)

L, L_inv = generate_affine_L(o,v)

return F, L, L_inv

When we run this key generation code for our simple example, we get the following private key. We can see that F is three homogenous quadratics where the entries in the matrices represent the coefficients of said quadratics. Note the 0 terms where oil and oil terms would have coefficients (they do not mix)! Moreover, we only need an upper-triangular matrix as i,j and j,i for all i,j in [1...n] would specify the same coefficient.

Private Key:

F (Central Map) =

0:

[[ 0 0 0 153 175 153 51 224 89]

[ 0 0 0 20 143 18 179 13 175]

[ 0 0 0 74 231 146 106 136 149]

[ 0 0 0 248 197 59 50 41 57]

[ 0 0 0 0 213 77 187 165 54]

[ 0 0 0 0 0 97 154 37 163]

[ 0 0 0 0 0 0 93 246 71]

[ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 181 188]

[ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3]]

1:

[[ 0 0 0 71 26 115 9 248 114]

[ 0 0 0 31 53 162 77 82 46]

[ 0 0 0 254 178 43 219 124 196]

[ 0 0 0 150 85 216 38 28 197]

[ 0 0 0 0 147 73 216 111 98]

[ 0 0 0 0 0 30 140 222 36]

[ 0 0 0 0 0 0 108 54 105]

[ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 253 38]

[ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 55]]

2:

[[ 0 0 0 98 27 252 165 31 42]

[ 0 0 0 180 169 247 143 217 128]

[ 0 0 0 13 111 90 98 40 233]

[ 0 0 0 223 243 229 156 183 45]

[ 0 0 0 0 40 136 12 123 44]

[ 0 0 0 0 0 251 92 77 174]

[ 0 0 0 0 0 0 81 150 95]

[ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 196 207]

[ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 108]]

Further, we show L and L_inv and confirm that they were generated correctly as their product is the identity matrix, that is L · L_inv= I.

Secret Transformation L=:

[[ 0 207 67 204 15 76 173 14 42]

[193 54 49 19 64 222 93 165 108]

[102 211 114 71 22 229 187 221 194]

[196 251 77 219 159 4 110 107 241]

[ 78 88 49 133 238 243 17 125 203]

[ 95 159 145 105 221 55 185 165 24]

[ 45 55 31 37 149 168 4 21 48]

[163 127 150 135 56 210 241 110 25]

[222 3 207 202 136 66 121 18 119]]

Secret Inverse Transformation L_inv=:

[[127 172 42 59 73 10 183 116 70]

[ 33 153 229 239 106 99 227 54 51]

[218 196 248 10 124 46 25 73 128]

[ 15 36 200 28 138 156 210 164 229]

[114 107 134 126 40 230 238 249 70]

[ 88 100 51 161 145 52 157 138 130]

[208 188 30 227 66 116 191 100 183]

[172 88 227 121 142 132 247 223 18]

[138 145 247 168 180 35 185 149 67]]

Confirming L is invertible as L*L_inv is I=:

[[1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0]

[0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0]

[0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0]

[0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0]

[0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0]

[0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0]

[0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0]

[0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0]

[0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1]]

Public (Verification) Key

We compute our public verification key by computing L ∘ f for each f in F. This is made easy as we can do this in quadratic form, thus each f_p in P is computed as L_T · f · L for each f in F where L_T is the transpose of L.

def generate_public_key(F,L):

L_T = np.transpose(L)

P = []

for f in F:

s1 = np.matmul(L_T,f)

s2 = np.matmul(s1,L)

P.append(s2)

return P

The following is our collection of o=3 polynomials that make up our public verification key P again represented as a list of matrices, that result from the above calculation using F and L that we generated as our private key.

Public Key = F ∘ L =

0:

[[246 74 117 248 72 5 143 224 135]

[116 10 17 156 68 243 203 128 192]

[148 215 239 220 212 65 184 253 214]

[211 116 203 186 61 26 104 21 157]

[155 87 23 174 10 242 98 215 238]

[189 209 203 142 221 105 179 173 8]

[109 27 161 201 155 133 197 180 66]

[227 228 150 92 248 73 213 205 192]

[ 51 30 193 111 242 244 74 177 154]]

1:

[[ 92 131 253 40 192 243 101 228 217]

[114 70 34 148 150 144 29 53 193]

[127 161 2 248 42 126 245 122 175]

[249 59 218 30 46 114 58 214 97]

[ 12 212 246 155 93 76 168 162 120]

[108 53 107 153 7 216 233 137 93]

[249 177 82 164 4 117 25 179 152]

[107 105 135 34 189 97 53 29 38]

[140 127 214 137 206 171 45 109 110]]

2:

[[156 73 34 203 141 187 88 54 168]

[ 90 252 145 72 161 130 93 150 169]

[112 158 75 6 174 157 206 192 193]

[214 198 116 243 190 194 214 22 5]

[ 74 231 235 113 151 91 75 122 123]

[200 77 208 125 99 169 229 104 55]

[184 128 22 88 42 170 139 233 189]

[ 27 149 64 89 77 158 248 65 150]

[ 93 59 212 106 143 221 24 178 242]]

Signing

To sign we first define some helper functions. The first picks v=6 random vinegar variable values rvv as specified in the signing algorithm.

def generate_random_vinegar(v):

vv = np.random.randint(256, size=v, dtype=np.uint8)

rvv = GF256(vv)

return rvv

We then substitute this selection of random vinegar variables rvv in each f in F, collecting terms such that the only remaining unknowns will be o1,o2,o3 – our oil variables.

def sub_vinegar_aux(rvv,f,o,v):

coeffs = GF256([0]* (o+1))

# oil variables are in 0 lt;= i lt; o

# vinegar variables are in o lt;= i lt; n

for i in range(o+v):

for j in range(i,o+v):

# by cases

# oil and oil do not mix

if i lt; o and j =o and j gt;= o:

ij = GF256(f[i,j])

vvi = GF256(rvv[i-o])

vvj = GF256(rvv[j-o])

coeffs[-1] += np.multiply(np.multiply(ij,vvi), vvj)

# have mixed oil and vinegar variables that contribute to o_i coeff

elif i = o:

ij = GF256(f[i,j])

vvj = GF256(rvv[j-o])

coeffs[i] += np.multiply(ij,vvj)

# condition is not hit as we have covered all combos

else:

pass

return coeffs

We collect the equations once the fixed random vinegar variables have been substituted (only leaving our unknown oil variables). This will be a linear system of o=3 equations in o=3 unknowns – which is easy to solve!

def sub_vinegar(rvv,F,o,v):

subbed_rvv_F = []

for f in F:

subbed_rvv_F.append(sub_vinegar_aux(rvv,f,o,v))

los = GF256(subbed_rvv_F)

return los

To solve the system we separate the coefficients on the unknown oil variables M from the constant terms c. We then take our message m (which is an element of length o in GF(256)) and subtract c from it to form the y that we need to find a solution x for. We then solve for said x. Finally, we compute the signature s for m by stacking x with the selected random vinegar variables rvv and taking s as the product of the inverse of our secret transformation L_inv and the stacked solution x and the random vinegar variables rvv.

def sign(F,L_inv,o,v,m):

signed = False

while not signed:

try:

rvv = generate_random_vinegar(v)

los = sub_vinegar(rvv,F,o,v)

M = GF256(los[:, :-1])

c = GF256(los[:, [-1]])

y = np.subtract(m,c)

x = np.vstack((np.linalg.solve(M,y), rvv.reshape(v,1)))

s = np.matmul(L_inv, x)

signed = True

except:

signed = False

return s

For this example we select m=[10,25,11] to be Évariste Galois’s – the father of finite fields – birthday.

m =

[[10]

[25]

[11]]

We then select our random vinegar values rvv.

rvv = [120 104 210 3 0 154]

After substitution we are left with the following M.

M =

[[252 223 17 183]

[200 254 141 176]

[116 200 15 43]]

We separate out the constant terms c of the linear oil system and subtract them from the message values m and solve the linear system using Gaussian elimination.

y = m-c =

[[10]

[25]

[11]]

-

[[183]

[176]

[ 43]]

=

[[189]

[169]

[ 32]]

f(o1,o2,o3) =

[[252 223 17]

[200 254 141]

[116 200 15]]|[[189]

[169]

[ 32]]

This yields the solution o1,o2,o3 =

[[68]

[49]

[94]]

We stack this solution x with our random vinegar variables rvv to form a complete solution to the non-linear multivariate polynomial system of equations:

[x | rvv] =

[[ 68]

[ 49]

[ 94]

[120]

[104]

[210]

[ 3]

[ 0]

[154]]

We can check out solution by plugging them into the central map.

m = x_T · F · x =

[[10]

[25]

[11]]

We see that this check works and we finally we compute our signature as:

s = L_inv · x =

[[ 50]

[ 79]

[107]

[122]

[209]

[241]

[ 80]

[173]

[241]]

Verification

To verify the message we simply compute P(s1,s2,...,sn) and check that the result (our computed message) is equal to the corresponding original message. This is made easy as we can do this in quadratic form, thus for each f_p in P we compute s_T · f_p · s where s_T is the transpose of s.

def verify(P,s,m):

cmparts= []

s_T = np.transpose(s)

for f_p in P:

cmp1 = np.matmul(s_T,f_p)

cmp2 = np.matmul(cmp1,s)

cmparts.append(cmp2[0])

computed_m = GF256(cmparts)

return computed_m, np.array_equal(computed_m,m)

Now let’s see if our signature is correct given our public_key and message.

computed_message = s_T · P · s=

[[10]

[25]

[11]]

computed_message == message is True

Hey, it works!

Exhaustive Test

As a sanity check we wrote a test function that generates a random private, public key pair for small parameters o=2, v=4. We continue to work over the field GF(256). With these parameters note that the messages we will be signing will be of field elements in GF(256) of length 2. As field elements taken on values in the range 0 to 255 there are 256**2 = 65536 total messages in the message space. We generate all messages in the message space and check that we can generate valid signatures for all of them.

# test over the entire space of messages for small parameters

def test():

o = 2

v = 4

F, L, L_inv = generate_private_key(o,v) # signing key

P = generate_public_key(F,L) # verification key

total_tests = 0

tests_passed =0

for m1 in range(256):

for m2 in range(256):

total_tests+=1

m = GF256([[m1],[m2]])

s = sign(F,L_inv,o,v,m)

computed_m,verified = verify(P,s,m)

if verified:

tests_passed+=1

print(f"Test: {total_tests}\nMessage:\n{m}\nSignature:\n{s}\nVerified:\n{verified}\n")

print(f"{tests_passed} out of {total_tests} messages verified.")

We now look at the output of the test and see that we were able to generate signatures for every message in the message space. This instills confidence in the validity of our implementation. The full test_results.txt file for one random key pair is included in the GitHub repository of our implementation that is linked above.

Test: 1

Message:

[[0]

[0]]

Signature:

[[ 53]

[211]

[161]

[ 6]

[228]

[124]]

Verified:

True

.

.

.

Test: 65536

Message:

[[255]

[255]]

Signature:

[[144]

[ 98]

[143]

[ 0]

[124]

[122]]

Verified:

True

65536 out of 65536 messages verified.

Concluding Remarks

Multivariate cryptography has seen renewed interest recently due to the call for the standardization of post-quantum cryptography. Recall that the main issue with UOV signature schemes are that the public keys are huge. Many contemporary schemes have tried to solve this issue. For instance, Rainbow is a scheme based on a layered UOV approach that reduces the size of the public key. It was selected as one of the three NIST Post-quantum signature finalists. However, a key recovery attack was discovered by Beullens and Rainbow is no longer considered secure. Note, this attack does not break UOV, just Rainbow. Furthermore, MAYO was put forth as a possible post-quantum signature candidate in NIST’s call for additional PQC signatures. MAYO uses small public keys comparable to that of lattice based schemes that are “whipped-up” during signing and verification – for details go to the MAYO website. In addition to exploring Rainbow and MAYO, in may interest the reader to explore Hidden Field Equations, which is another construction of multivariate cryptography schemes.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Paul Bottinelli and Elena Bakos Lang for their thorough reviews and thoughtful feedback on this blog post. All remaining errors are the author’s.